This section will describe the dataset as I first compiled it. This base dataset consists of the records for three years of metadata describing articles from the journal American Literature, downloaded from MLA International Bibliography. For each year, I created a human-readable .txt file by copying and pasting from the HTML page produced by EBSCO’s “Save” function.

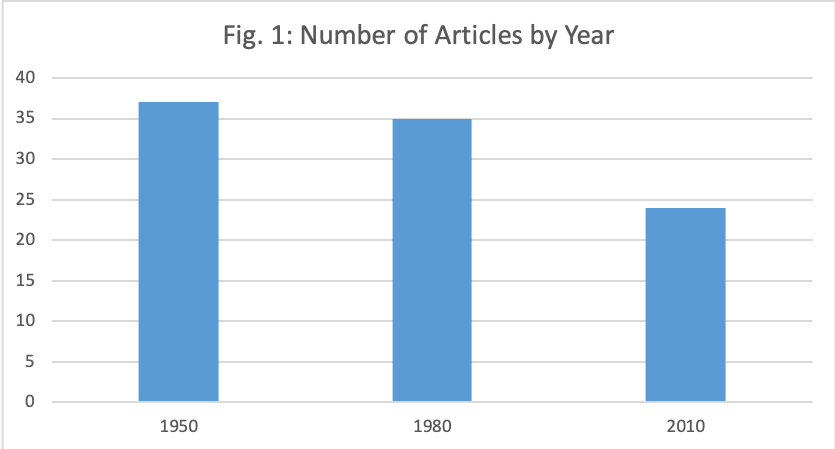

Although each file covers a year’s worth of articles published in this journal, they are not equal in number. The number of articles is as follows:

-

- 1950: 37 articles

- 1980: 35 articles

- 2010: 24 articles

I extracted the subject terms for further examination. To limit the scope of the project, the other metadata fields (article titles, author names, etc) were not used.

Structure of the Data

My search in MLAIB captured metadata about this journal, rather than the text of the journal itself. Thus, I was already at one remove from the articles themselves. While the Bibliography indexes all the scholarly articles published in American Literature, it does not capture all the journal’s content, since it excludes book reviews. It also does not capture the distinctions made within the journal’s structure between longer articles and what the journal calls “Notes and Queries.” Thus, while MLAIB represents the scholarly content of this journal, it doesn’t represent everything published there.

More subtly, however, the way that the data is structured is also a representation by the Bibliography. MLAIB uses a database with a graphic user interface (GUI). GUIs are relatively user-friendly and often straightforward, but they also limit what data a user is able to access. The data we’ve downloaded so far is in a plaintext format, so the structure of the data is visible but not yet manipulable; if I had access to the back end of the bibliography, I could have accessed the structured data directly. Furthermore, the variation among searchable fields in different vendor platforms suggest that there are differences between the fields that exist in the database and the fields made available for users to view and search.

Structure of a Record

At this point, let’s take a moment to look at the way that data we retrieved is structured in the database. Each piece of information gathered about the article is slotted into a particular category, like “author” or “subject term.” These categories are called “fields.”

Let’s look at one example. This is part of the record for the following journal article: Stadler, Gustavus. “Louisa May Alcott’s Queer Geniuses.” American Literature: A Journal of Literary History, Criticism, and Bibliography, vol. 71, no. 4, 1999, pp. 657-77. Note that the parts of this record that give technical information about the article aren’t needed for this analysis and have been excluded.

Title: Louisa May Alcott’s Queer Geniuses

Authors: Stadler, Gustavus

…

Source: American Literature: A Journal of Literary History, Criticism, and Bibliography (AL)

1999 Dec; 71 (4): 657-77. [Journal Detail]

Peer Reviewed: Yes

…

General Subject Areas:

Subject Literature:

American literature

Period: 1800-1899

Primary Subject Author:

Alcott, Louisa May (1832-1888)

Primary Subject Work: Little Women (1868); ‘The Freak of a Genius’

Classification: novel

Subject Terms:

treatment of gender; of genius; homosexuality

Document Information:

Publication Type: Journal Article

Language of Publication:

English

…

In this case, the subject literature is American, because Alcott is an American author. The period, 1800-1899, tells us that Little Women was published in the nineteenth century. Alcott is the primary subject author, and her works Little Women and “The Freak of a Genius” are the primary subject works, because those are the works analyzed in this article. The subject terms give us more information as to what this article is about; Stadler analyzes the treatment of gender, the treatment of genius, and the treatment of homosexuality.

The subject terms included in MLAIB make searching the database much easier. It’s possible to find all the articles on Alcott or on Little Women, and it’s even possible to do some searching according to the subject matter of the criticism; this article would be returned in a search on gender, even though the word “gender” is mentioned nowhere in the title. However, this sort of subject term is less consistently included throughout the database than the terms describing primary author, work, and national literature. Additionally, the vocabulary of subject terms changes over time; some terms are no longer used, and others are new. Therefore, scholarly consideration of the terms used serves not only as a measure of what is of interest to the publishers of American Literature (and, presumably, their readers), but also the concerns of the bibliography and its field bibliographers.

Knowing this structure is important because I used the structure of the record to extract the data for the subject areas mentioned above — period, subject author, and so forth. The results of this process became the data that I transformed throughout the remainder of this analysis.

Records in the bibliography constituted data for us, but looking at this record, it’s clear that many choices had already been made by the time we accessed the records. When selecting which fields to include in the records they produce, the editors of the bibliography decided which characteristics of an item were important enough to include in its description, and have structured the database around these decisions. This is why it’s easy to ask questions about which authors are the subjects of articles, but much more difficult, for instance, to ask questions about which authors had mental illnesses. The tractability of any dataset is shaped by the decisions made when it was originally made available.

The vendor platforms also made choices as they added their own structure to the metadata. Note that the Gale and EBSCO search interfaces use different language to describe the fields, and may in fact yield different results in searches. Most notably for our purposes, EBSCO breaks out the different types of subject terms, while Gale simply presents an unstructured list. The structure behind the subject terms exists and can be searched in Gale, but their structure is not visible to end users in the record itself.

The choice of EBSCO allowed me to access this structure, so I could analyze subject authors and works separately from the descriptive subject terms.

Creating the Dataset

Due to copyright restrictions, I cannot share the records I retrieved on the website. However, I can explain exactly how I did it, and will share later, transformed stages of my dataset under fair use.

I retrieved the records for all the articles published in American Literature for three separate years, 1950, 1980, and 2010.

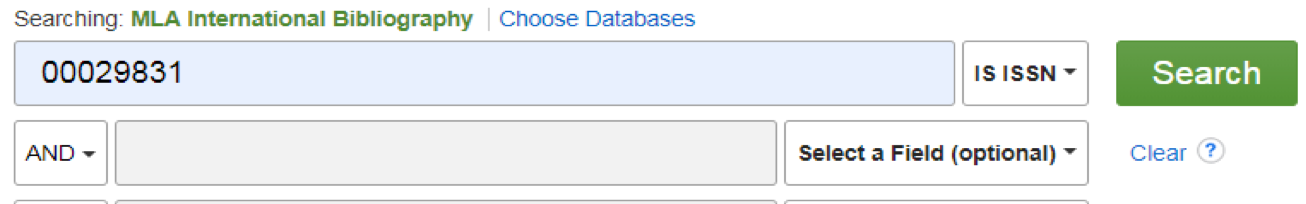

To get the records from MLAIB, I did three separate searches, one for each year. Because other journal titles may include the phrase “American literature,” I searched by ISSN — a standardized number for identifying periodicals, similar to ISBN for books. American Literature’s ISSN is 0002-9831. For each search, I limited by date to the appropriate year.

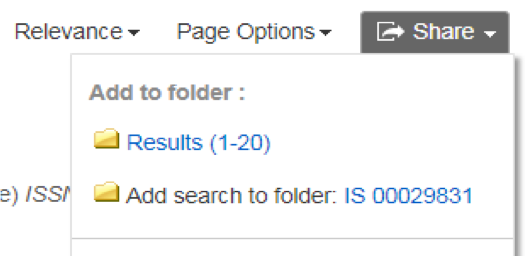

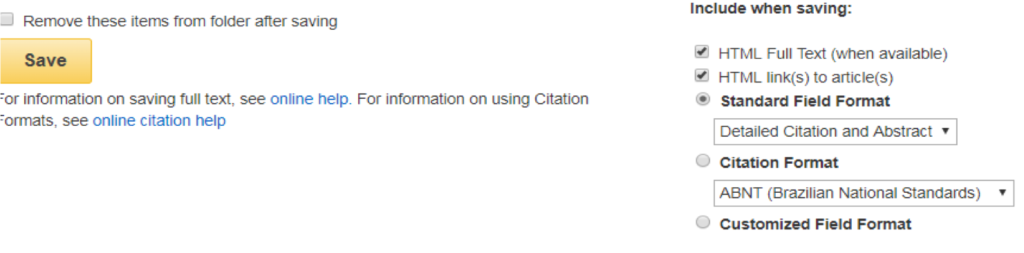

The EBSCO interface includes a “Share” button, which allows the user to add one (20-item) page of results to the folder at a time, so I clicked through and added each page.

From the folder, it is possible to save up to fifty results at a time. This limitation presents another strong argument against working with a large dataset.

For each year, I obtained:

-

- A CSV file, which can be downloaded by using the “export” function in the folder and the “Download as CSV” option there.

- A plain text file. This data was obtained via the “Save As File” option in the folder and copied into a text file.

I did not use the CSV files because, while they had separate fields for the articles’ bibliographic information like author and title, they didn’t split out the subject terms. Instead, all subject terms for each record appeared within a single field. However, the CSVs could be useful for other kinds of analysis.