Offering conclusions is less important to this project than walking through the data, but let’s take a moment to think about what sorts of questions we could answer at the end of this process — and what further questions our work raised!

All the data here is based on counting subject terms, not the articles in which they appear. That is, an article may analyze several authors, or consider several different types of work — or indeed, include multiple terms describing similar types of works.

However, I’m still including the nulls where they’re relevant, because they show interesting patterns, too.

The analysis will be split up just as the data was, starting with American Literature by Century.

American Literature by Century

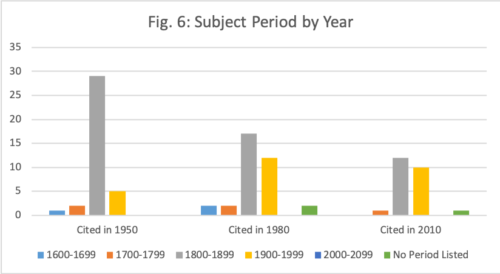

The transformation that produced this data

The journal American Literature, at least in the years I considered, seems to focus very strongly on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. As time passes, the twentieth century grows in importance as the nineteenth recedes slightly; this is unsurprising given that our first dataset occurs exactly in the middle of the twentieth century (1950)! It would make sense if more time were needed for critics to begin publishing articles about twentieth century authors in major journals. The lack of any twenty-first century work in 2010 could be explained by the same reasoning, although it would be interesting to return to this data in thirty years or so, and see whether twenty-first century literature is as prevalent in the 2050 issues of American Literature as twentieth-century literature was in the 1950 issues.

Nineteenth-century literature seemed to recede between 1950 and 1980, but not to change much between 1980 and 2010. That’s interesting; I’d like to check whether that’s true in adjacent years like 1980 and 2011, and whether it’ll still be true in the 2050 publication.

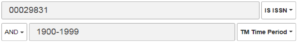

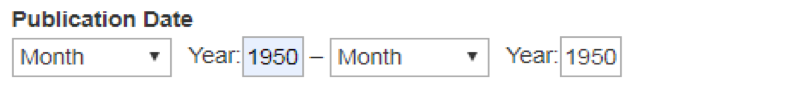

Some of these questions could be answered with simple MLA searches, like this:

With a few such searches, we could get a pretty good idea of the number of articles covering a particular time period over each decade (though of course, we wouldn’t get the nulls, so we wouldn’t know how many articles were published without being assigned to a specific time period).

On the other hand, questions about the future have to wait (this is the data TRIKE, not the data TARDIS).

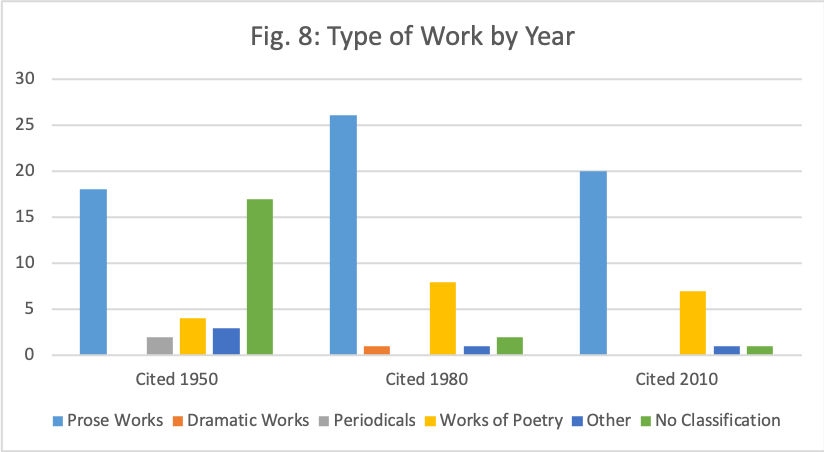

American Literature by Type of Work

The transformation that produced this data

This journal focuses on prose and includes a little work on poetry, and does not seem to emphasize drama at all. It’s possible — indeed, likely — that we’d find much more work on drama in other years, but in the three years we considered, only one work of drama was identified in the metadata, which suggests that drama probably isn’t central to the scope of the journal.

Again, we could search the database for works on drama in American Literature, to see whether this pattern holds.

Major changes in type of work over time aren’t evident here either – these same patterns seem true of all three years.

However, we can also see some changes that are probably related to MLA’s indexing system. When we considered both “classification” and “genre” together, the number of works not listed by type dropped dramatically, suggesting that MLA has become much more consistent about classifying works by type or genre. It also appears that the “genre” category is being used much more than previously. To understand this better, I’d probably need to look into whatever documentation the MLA and/or EBSCO provide about the fields used in the bibliography, and perhaps to talk with people there. Not all the answers exist in the data, even if we could collect more of it.

American Literature by Authors

The transformation that produced this data

A lot of authors were featured here! As I mentioned in the data transformation, there are so many authors in the data that it’s difficult to draw any conclusions about the relative importance of any particular figure in the field as the journal helps to construct it. Even Melville, who is by far the most common subject author, may not be as central as he seems, considering the decrease in mentions from 1950 to the other two years.

We can, however, draw a few conclusions about whose literature is the subject of the journal and how that’s changed.

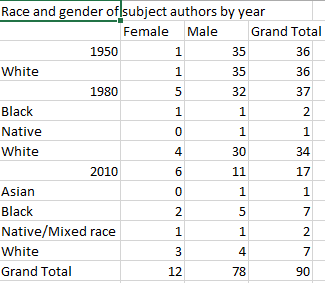

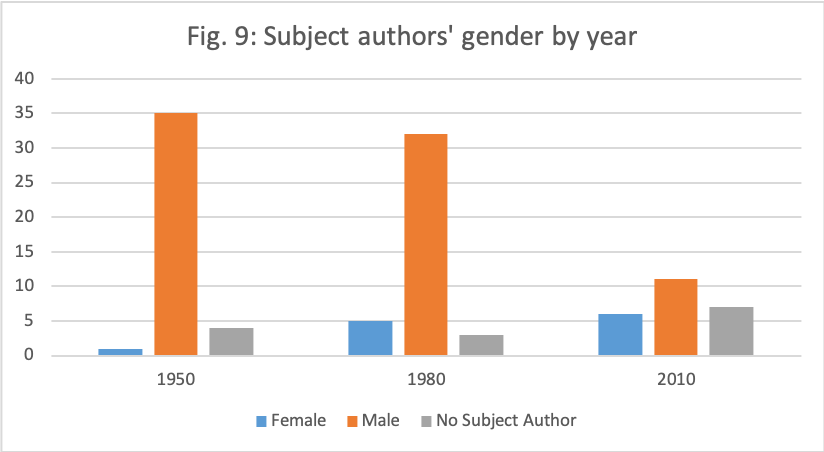

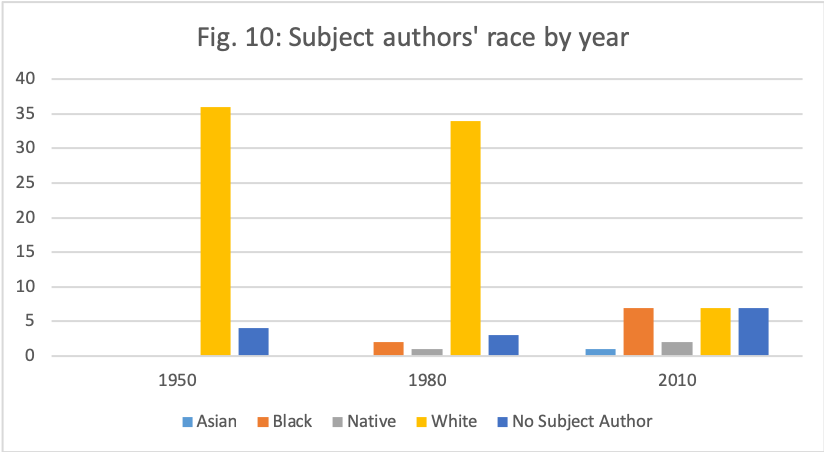

In 1950, American Literature published articles about white male authors and one on Willa Cather. 1980 included a few more female, black, and Native authors, but was still overwhelmingly white and male. 2010 looked a little different, but also included far fewer articles overall — so just a few more articles on female authors and authors of color changed the overall proportions a lot. This still doesn’t mean that they are publishing a lot more articles about female authors and authors of color, necessarily — for instance, the move from one article about a Native American author in 1980 to two such articles in 2010 probably doesn’t amount to much, even if it does account for a much larger proportion of the journal’s content for that year.

Still, it appears that the journal is paying more attention to a more diverse group of American writers, or at the very least, its leadership has realized it isn’t acceptable to put out an issue of a scholarly journal on American literature that considers only white, male authors. This is hopeful, and it’s another kind of analysis I’d like to do with a larger group of issues.

However, unlike the subject works by year queries mentioned above, these questions are much more difficult to answer with a quick search of the database, because the metadata doesn’t support them! The “group” field attempts to support this kind of query, but does so very inconsistently.

American Literature by Subject

The transformation that produced this data

This is by far the most complex of the fields that we’ve considered! It draws on a large, previously determined vocabulary of terms, and this vocabulary probably has a structure to which we as researchers did not have access. The vocabulary itself has probably changed over time — some terms have been replaced, new terms added, and older ones removed. Additionally, the task of assigning this vocabulary is more complex than any of the others we’ve considered; it addresses many different aspects of the work, and it requires many more judgement calls on the part of the indexers.

However, this is also extremely interesting data. If we found a way to understand it, it could help us to identify not only the general subject matter the the journal is publishing, but also what sorts of things scholars who publish in it are saying. We should remember, though, that this data is based on multiple layers of interpretation — first, the indexers’ interpretations of the articles published in the journal, and then, my interpretation of the terms the indexers assigned, as manifested in the codes I applied to them.

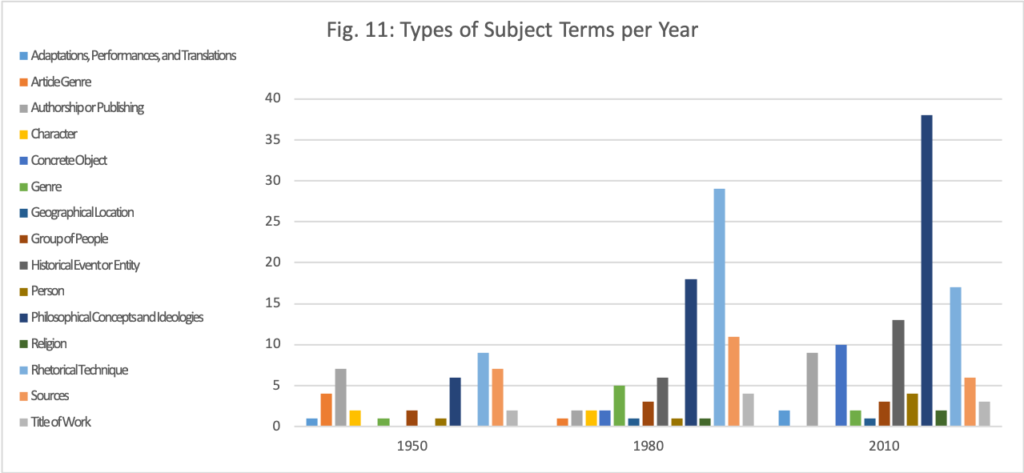

This chart isn’t very legible because it has so many categories, but a few patterns quickly become obvious.

Number of Subject Terms

| 1950 | 1980 | 2010 | |

| Number of Subject Terms | 44 | 95 | 112 |

| Number of Articles | 37 | 35 | 24 |

| Articles without Subject Terms | 17 | 2 | 0 |

| Subject Terms per Article | 1.189 | 2.714 | 4.667 |

The table illustrates the increase in the number of subject terms assigned. The average number of terms per article doubled between 1950 and 1980; it didn’t quite double between 1980 and 2010, but it did increase dramatically, such that 2010 has more terms overall than any other year, despite having fewer articles. This probably tells us more about MLAIB than it does about American Literature (or American literature). Indexers are assigning more terms now. This could be happening for several reasons:

- Improvements in technology made it much more practical to have several index terms for the same item. A print index is constrained by its size in ways that a computerized one is not, and processing power has increased considerably.

- The vocabulary of subject terms has almost certainly grown, giving indexers more options when assigning terms.

- Searchers may be more reliant on index terms, thus encouraging MLA to be more comprehensive when assigning them.

- As the importance of this resource has grown, they may be using more indexers than they did in the past, thus giving each indexer more time to work on any given article.

Without further researching the history of the Bibliography, we don’t know which of these explanations, if any, is true. This could be a good research question; I’m sure there is some kind of story here.

Since articles published in 2010 have nearly four times as many subject terms on average as those published in 1950, it isn’t necessarily meaningful to show that a particular term or set of terms were used more often in 2010.

Types of Subject Terms

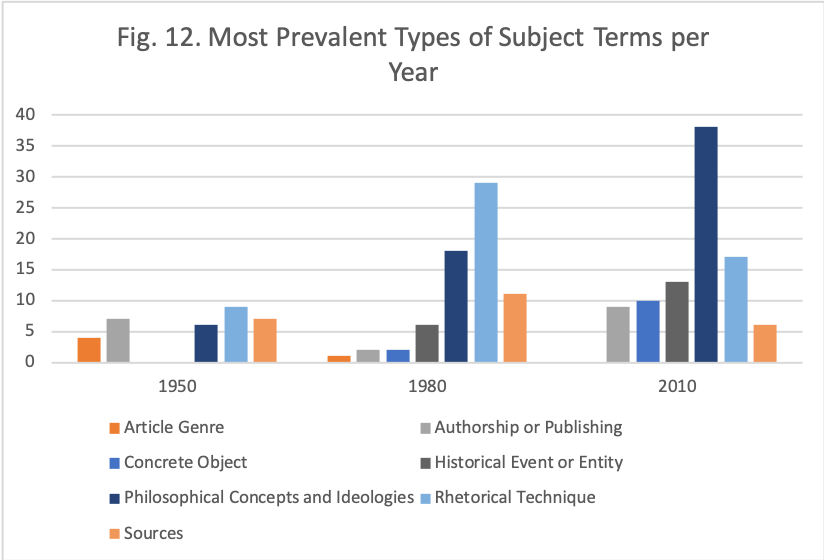

Some of the types of subject terms have definitely increased or decreased in prevalence. It’s possible, of course, that some of this is an artifact of my coding, but some of the biggest categories have shifted in ways that fit well with my understanding of the history of the field. Another chart, showing only the terms that comprise at least 5% of the terms assigned, either overall or in any one of the three years, makes these patterns a little clearer.

The terms relating to philosophical concepts were important every year, but have grown considerably from year to year. The terms I put in this category may be very different from each other, but have in common that they refer to concepts or ideas; they are the sort of terms that are often referred to as “themes.” Just as an example, the first several terms in this category alphabetically are:

- aesthetics

- black-white relations

- canon

- childhood

- civilization

These are all very different from each other, but they are more different from the other terms in this dataset. It might be interesting to see how the concepts referred to change from year to year; I’ve split them out to make that easier.

In any case, the jump in terms of this type is extremely noticeable. If I picked up a real effect here, does it suggest that criticism (or at least, this one journal) has come to focus more strongly on thematic concepts? Alternatively, as MLAIB assigns more terms, does it have more room for the more conceptual ones? It’s difficult to know for sure; going back to the original list of articles would likely help.

Two other notable patterns emerged here: the growth and decline of terms about rhetorical techniques, and the emergence of terms referencing historical entities or events. In general, without considering their application to these articles, these terms could be associated with different types of criticism. A focus of rhetorical techniques would fit with New Criticism, which seeks to draw meaning from the rhetorical characteristics of a work, while the historical terms suggest the use of historical approaches to literature, including New Historicism, which considers works of literature as historically situated artifacts.* In our data, the use of terms describing rhetorical techniques, including terms like “allegory,” “caricature,” and “dialogue,” are always present, but peak in 1980. In contrast, historical terms like “abolitionist movement,” “King Philip’s War,” and “treatment of labor strike” emerge in 1980, but there are many more of them in 2010. Again, I invite you to examine these terms yourself:

The varying prevalence of these types of terms matches very well with the history of these two types of criticism. New Criticism was very popular in the mid-twentieth century through the nineteen-seventies, but in the later part of the twentieth century, it declined in favor of other theories of literary criticism. This maps very well to the data we have. On the other hand, historical criticism has a long history, but the rise of New Historicism in the 1980s surely contributed to the publication of more articles about the intersection between literature and history. Additionally, the popularity of feminist criticism, post-colonial criticism, and similar critical interventions may help to explain the data we saw above; general concepts often fit well with these sorts of criticism.

Without a more thoroughly tested coding system, I cannot say for certain that these patterns are fully explained by changes in critical approaches over the years, but their reflection of these changes is a point in favor of the system I devised. Through this system, I’ve been able to notice the effects of some historical changes that I know took place; it’s pointing out some real changes in the content of the journal. Thus, I’m interested to know whether other changes, such as the increase in terms referencing physical objects (including bodies) also reflect changes in literary criticism. Again, the data I have does not justify my drawing a conclusion about that, but it does provide some encouragement to look further by considering additional years and looking at the articles themselves.

*Obviously, both of these are gross simplifications; please read further on each of these schools of criticism

Conclusion

What I’ve suggested here is really a place to begin. One of the things I find interesting about the analysis I’ve done here is that it serves mainly to point out new questions. This is a perfectly valid use for data, especially in the humanities — it tells you where to look.

Continue on to the statement of fair use…

Return to the table of contents…